History of the Stewarts | Battles and Historic Events

If you are a Stewart Society Member please login above to view all of the items in this section. If you want general information on how to research your ancestors and some helpful links - please look in background information.

If you have a specific question you can contact our archivist.

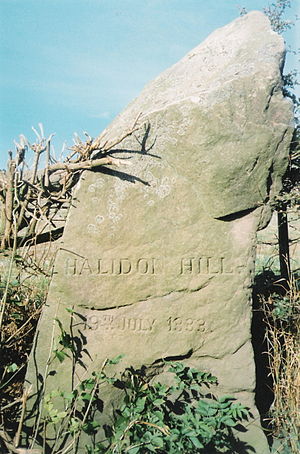

Battle of Halidon Hill

A decisive English victory 19th July 1333

Monument

In Scotland Archibald Douglas, brother of the "Good" Sir James Douglas, and now Guardian of the Realm for the underage David, made arrangements for the defence of Berwick-upon-Tweed. Weapons and supplies were gathered, and responsibility for the defence of the town was given to Sir Alexander Seton. These preparations were all complete by the time Balliol crossed into Roxburghshire on 10 March 1333. Besides the disinherited lords he was also accompanied by a number of English magnates. The army advanced quickly towards Berwick, which was placed under siege. Balliol was acting openly in the English interest. The Second War of Independence had begun

With the arrival of the English king the attack on Berwick began in earnest. Seton carried out a spirited defence; but by the end of June, under repeated attack by land and sea, his troops were close to exhaustion. He requested and was granted a short truce, but only on the condition that he surrender if not relieved by 11th July. As a guarantee of good faith Seton was required to hand over a number of hostages, which included his son, Thomas. Scotland was now faced with exactly the same situation that England had before Bannockburn: as a matter of national pride Douglas would have to come to the relief of Berwick, just as Edward II had come to the relief of Stirling Castle in 1314. The army the Guardian had spent so much time gathering was now compelled to take to the field, with all initiative lost. Nevertheless, Douglas´ force was an impressive representation of the nation´s strength and unity, with volunteers coming from all corners of the realm. Douglas now began his belated march to the border.

In an attempt to draw Edward away from Berwick, Douglas entered England on 11 July, the last day of Seton´s truce. He advanced eastwards to the port of Tweedmouth, in contested Northumberland. Tweedmouth was destroyed in sight of the English army: Edward did not move. A small party of Scots led by Sir William Keith managed with some difficulty to make their way across the ruins of the old bridge to the northern bank of the Tweed. Keith and some of his men were able to force their way through to the town. Douglas chose to consider this as a technical relief and sent messages to Edward calling on him to depart. This was accompanied with the threat that if he failed to do so the Scots army would continue south and devastate England.

Edward refused to consider Sir William´s entry into Berwick as a relief in terms of the agreement of 28 June. As the truce had now expired, and the town had not surrendered, he ordered the hostages to be hanged before the walls, beginning with Thomas Seton. A further two were to be hanged on each subsequent day for as long as the garrison refused to surrender. To save the lives of those who remained Seton concluded a fresh truce, promising to surrender if not relieved by Tuesday 20 July. Everything now hinged on a Scots victory in battle. News of this was carried to the Guardian at Bamburgh.

Edward and his army took up position on Halidon Hill, a small rise of some 600 ft. two miles to the north-west of Berwick, which gives an excellent view of the town and surrounding countryside. From this vantage point he was able to dominate all of the approaches to the beleaguered port. Any attempt by Douglas to by-pass the hill and march directly on Berwick would have been quickly overwhelmed. Crossing the Tweed to the west of the English position, the Guardian reached the town of Duns on 19 July. On the following day he approached Halidon Hill from the north-west, ready to give battle on ground chosen by his enemy. It was a catastrophic decision.

The Scots waited until after midday to attack, and marched across boggy ground to meet the English, but buckled under a hail of arrows. The bloodiest fighting was on the right half of the English line, where the battle continued throughout the day. Eventually the English won and pursued the remaining Scots northwards. Berwick fell the next day.

Halidon Hill was Edward III´s first real battle. Here he learnt how effective a combination of archers and men-at-arms could be. Later Crecy and Poitiers would show that the tactics first tested against the Scots work as well against the mounted knights of France.

The battlefield, which in 1333 was uncultivated scrub and marsh, is now a patchwork of fields.

Reference: Halidon Hill Battlefield Trust