History of the Stewarts | Battles and Historic Events

If you are a Stewart Society Member please login above to view all of the items in this section. If you want general information on how to research your ancestors and some helpful links - please look in background information.

If you have a specific question you can contact our archivist.

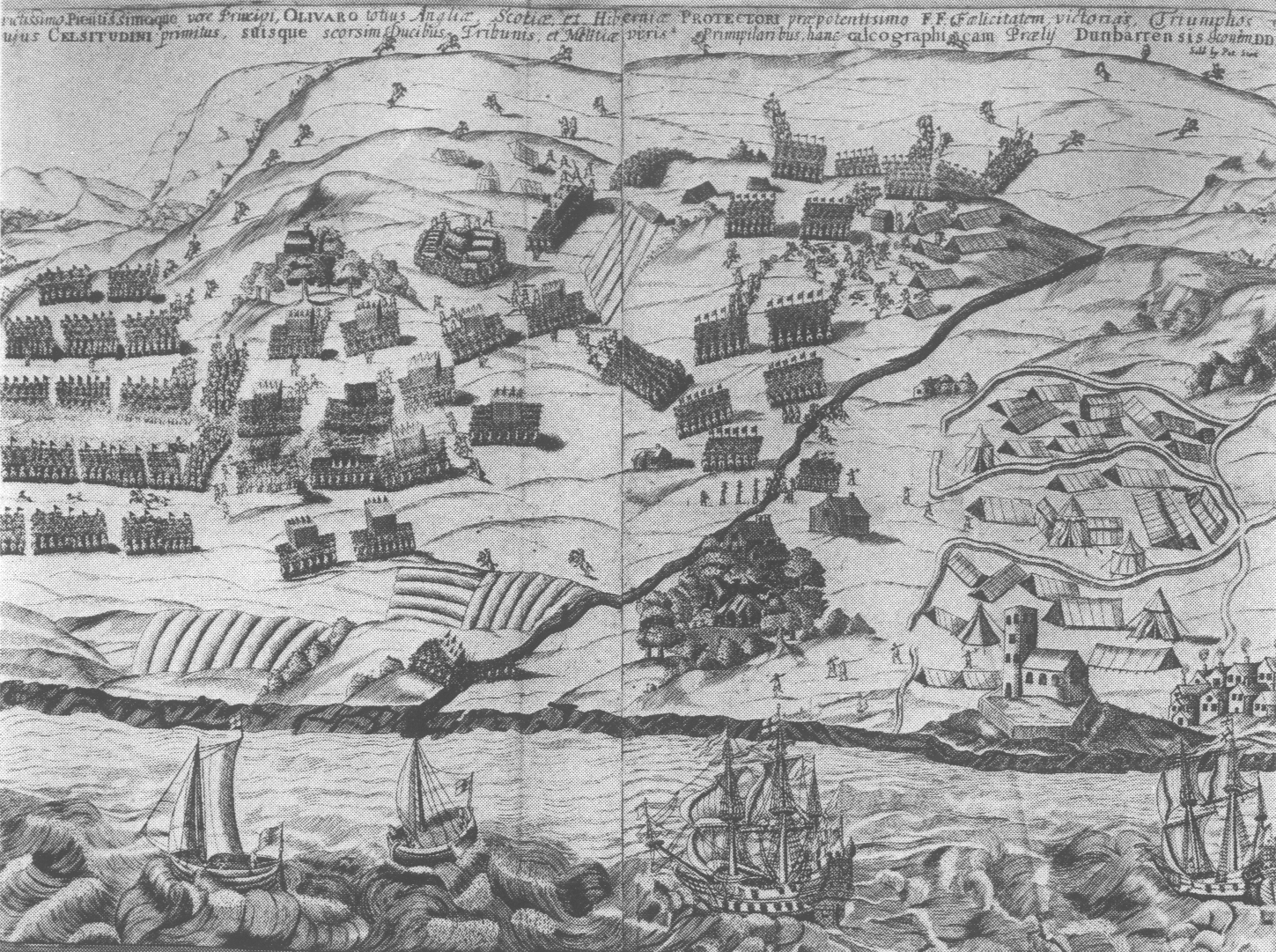

The second Battle of Dunbar

Oliver Cromwell led the English army and crossed the border on 22nd July 1650 and occupied Dunbar (in East Lothian) on the 26th. The Scottish general, Sir David Leslie, continued his deliberate strategy of avoiding a direct confrontation with the enemy. His army were not the battle-hardened veterans of the Thirty Years´ War who had taken the field for the Scots at Newburn and Marston Moor a few years before.. Many of these men had died during the Civil War and the unsuccesful 1648 invasion of England. Far more had left active service after the former event. This meant that a new army had to be raised and trained by the remaining veterans. Eventually the army comprised some 20,000 soldiers, outnumbering the English army of 11,000 men. Though the Scots were well armed, the pressure of time meant they were poorly trained compared with their English counterparts, all of whom had served with Oliver Cromwell for years. Leslie chose therefore to barricade his troops behind strong fortifications around Edinburgh and refused to be drawn out to meet the English in battle. Furthermore, between Edinburgh and the border, Leslie adopted a scorched earth policy thus forcing Cromwell to obtain all of his supplies from England, most arriving by sea through the port at Dunbar.

Whether in a genuine attempt to avoid prolonging the conflict or whether because of the difficult circumstances he found himself in, Cromwell sought to persuade the Scots to accept the English point of view. Claiming that it was the King and the Scottish clergy who were his enemies rather than the Scottish people, he wrote to the General Assembly of the Kirk on 3 August famously pleading, "I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken." This plea, however, fell on deaf ears.

By early September, the English army, weakened by illness and demoralised by lack of success, began to withdraw towards its supply base at Dunbar. Leslie, believing that the English army was retreating, ordered his army to advance in pursuit. The Scots reached Dunbar first and Leslie positioned his larger army on Doon Hill on the eastern edge of the Lammermuir Hills, overlooking the town and the Berwick Road, which was Cromwell´s land route back to England.

However, the Scots army manoeuvred itself into a new position which was subsequently regarded as a tactical blunder. Eager to curtail the mounting cost of the campaign, the Kirk ministers in attendance are said to have put Leslie under great pressure to finish the battle quickly. On 2 September 1650, he brought his army down from Doon Hill and approached the town, hoping to secure the road south over the Spott Burn in preparation for an attack on Cromwell´s encampment. Cromwell at the same time probably began to make preparations for a dash into England. At this point. it is unlikely he had any serious hopes of defeating the Scots army. However, witnessing Leslie´s men wedge themselves between the deep ditch of the burn, and the slopes of the Lammermuirs behind them, he knew that an attack on the Scottish right flank would leave the left flank unengaged and that a successful push against the right would roll the latter back. On observing the manouevre, he is said to have exclaimed, "The Lord hath delivered them into our hands!"

That night, under cover of darkness, Cromwell stealthily redeployed a large number of his troops to a position opposite the Scottish right flank. Just before dawn on 3 September, the English troops, shouting their battle cry "The Lord of Hosts!", launched a surprise frontal attack on the Scots, while Cromwell engaged their right flank. Soldiers in the English centre and on the right caught Leslie´s men unawares but were held at bay by the long pikes of their Scottish opponents. The right flank of the Scots, however, with less freedom to manoeuvre, was pushed back under the weight of superior English numbers until its lines started to disintegrate. Cromwell´s heavier horse then clashed furiously with the more lightly armed cavalry of the Scots and succeeded in scattering them. Observing this disaster, the rest of the Scottish army, hopelessly wedged between the Spott or Brox Burn and Doon Hill, lost heart, broke ranks and fled.In the rout that followed, the English cavalry drove the Scots army from the field in disorder. Cromwell reported to Parliament that the "chase and execution" of the fleeing Scots had extended for eight miles.

Cromwell claimed that 3,000 Scots were killed. On the other hand, Sir James Balfour, a senior officer with the Scottish army, noted in his journal that there were "8 or 900 killed". There is similar disagreement about the number of Scottish prisoners taken: Cromwell claimed that there were 10,000, while the English Royalist leader, Sir Edward Walker put the number at 6,000, of which 1,000 sick and wounded men were quickly released.The more conservative estimates of the Scottish casualties are borne out by the fact that, the day after the battle, Leslie retreated to Stirling with some 4,000-5,000 of his remaining troops. The Scots prisoners, of which there were thousands, were marched to Durham Cathedral to be imprisoned. Many died enroute and of those that survived many were transported.

The Battle of Dunbar is seen as Cromwell´s greatest victory, despite how close he came to defeat. It also meant that since the leadership by the Kirk party was now seen as ineffectual - Scotland turned to Charles II.

Reference: The Battle of Dunbar - Battlefields Trust